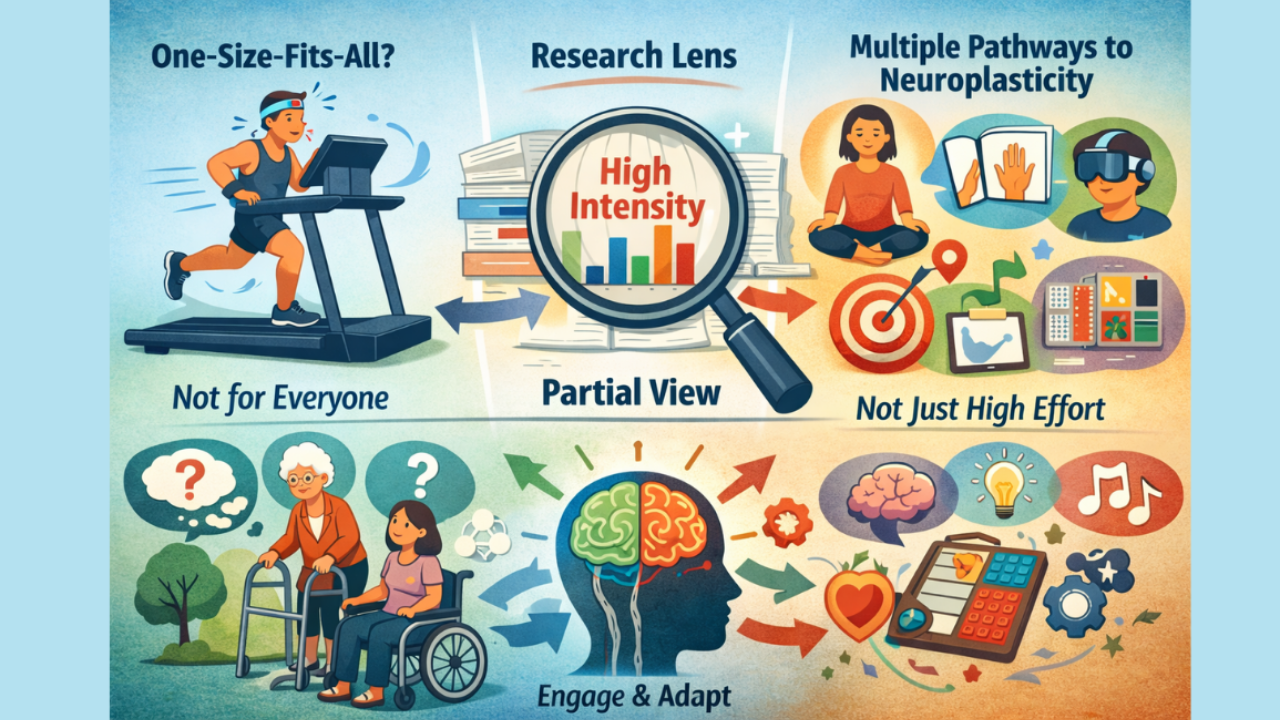

When Rehab Isn’t “High Intensity” — Is It Still Enough?

Feb 12, 2026

There’s a quiet fear many rehab clinicians and patients share:

If we’re not pushing high intensity… are we doing enough to change the brain?

We’ve all seen the messaging.

High reps. High load. Forced use. Bootcamp-style recovery.

“More is better” gets repeated so often it starts to sound like a rule.

But neurorehabilitation is not a gym competition.

And the truth is more nuanced — and more hopeful.

Let’s unpack the fear, the science, and what the research actually supports.

The Fear Behind Low-Intensity Work

The concern is understandable.

If neuroplasticity is experience-dependent…

and repetition drives change…

then it feels logical to assume:

Lower intensity = weaker results

Clinicians worry they’re underdosing.

Patients worry they’re wasting precious recovery time.

But recovery is not a linear volume equation.

The brain doesn’t only respond to force and fatigue.

It responds to attention, novelty, salience, error, and meaning.

Intensity is one pathway to plasticity — not the only one.

1. Not All Approaches Work for All Brains

One of the most important realities in rehabilitation:

There is no universal protocol that works for everyone.

Two people with the same diagnosis can respond completely differently to the same intervention.

Why?

Because neuroplasticity is shaped by:

-

lesion location

-

cognitive capacity

-

emotional regulation

-

fatigue tolerance

-

sensory processing

-

motivation

-

learning style

-

prior experiences

-

sleep and stress

-

medication effects

A patient who shuts down under high physical demand may learn more from distributed, low-load, cognitively engaging practice.

Another patient thrives under intensity.

Both can produce meaningful plastic change — but through different routes.

Rehabilitation is not about copying protocols.

It’s about matching dose + style + nervous system.

2. Research Articles Show a Slice of Reality — Not the Whole Picture

This part is rarely discussed openly.

Research studies are designed to answer very specific questions.

Even literature reviews — which seem broad — are structured around a focused lens. Researchers select articles that fit inclusion criteria to answer their question. That means:

-

certain populations are excluded

-

certain intervention styles are excluded

-

real-world clinical variability is excluded

-

messy human factors are filtered out

This is not a flaw — it’s how science maintains clarity.

But it also means:

No single paper captures the full complexity of neurological recovery.

A study showing benefits of high-intensity training does not prove that lower-intensity strategies are ineffective.

It proves that in that sample, under those conditions, a specific approach produced measurable change.

Clinical practice lives in a broader ecosystem than any single study.

Evidence guides us.

It does not replace clinical reasoning.

3. For Those Who Want Validation: Research Supporting Neuroplastic Change Without Extreme Intensity

If you’re someone who needs reassurance that lower-load interventions still influence neurological recovery — the literature does support this.

Recent peer-reviewed work highlights multiple pathways to plastic change beyond brute physical intensity. These include cognitive engagement, emotional regulation, sensory enrichment, and task salience.

Examples discussed in contemporary neurorehabilitation research include:

-

motor imagery and action observation training

-

mirror therapy

-

cognitive-motor dual task training

-

virtual reality environments

-

goal-directed task practice

-

mindfulness and autonomic regulation strategies

-

sensory discrimination training

-

enriched environments

-

distributed (spaced) practice

-

task-specific cognitive training

Narrative and systematic reviews in the past few years emphasize that neuroplasticity is driven by engagement and network activation, not just muscular output. These approaches activate motor, sensory, cognitive, and emotional circuits that support cortical reorganization.

In other words:

The brain changes when it is challenged meaningfully — not only when it is exhausted.

That distinction matters.

The Bigger Picture

High intensity training has an important place in rehabilitation.

It is powerful.

It can accelerate gains in the right context.

But it is not the sole gatekeeper of recovery.

A nervous system that is overwhelmed cannot learn.

A patient who feels unsafe cannot engage deeply.

A brain in chronic fatigue cannot encode efficiently.

Sometimes the most neuroplastic intervention is not pushing harder —

it’s creating the conditions where learning can actually occur.

Recovery is not measured only by sweat.

It’s measured by adaptation.

What This Means for Clinicians and Patients

If you are a clinician:

You are not failing your patient by using thoughtful, lower-load interventions when appropriate. You are respecting nervous system capacity and matching the intervention to the person.

If you are a patient:

Recovery does not require constant maximal effort to be valid. Consistent, meaningful engagement with the right challenges drives change — even when it looks quieter from the outside.

The goal is not intensity for its own sake.

The goal is effective stimulation of the brain.

And there are many evidence-supported ways to get there.